Persuasive Technology: How Can We Make It More Ethical?

Have you read much about captology? It's not a term frequently used, but it addresses a pervasive issue in our now very digital world. Captology is the study of persuasive technology---it was coined in the 1990s by BJ Fogg based on an acronym for Computers As Persuasive Technologies. It looks at any technological devices or platforms that stem from an intention to persuade users' attitudes or behaviors in some way. Back in its beginnings, this new area of study brought up the issue of identifying and creating such technologies in ethical ways. Now, over twenty years later, the importance of that element has vastly intensified.

The popular documentary The Social Dilemma (from Jeff Orlowski, the director of Chasing Ice and Chasing Coral) illuminates this: persuasive technologies, particularly in social media, are frequently used in ways that profit from users' disadvantage and ill mental health---often without the users stopping to realize it. How can we address this problem, and how should we? Let's start with a brief overview of captology and a look at its potential for applications among today's digital challenges.

The Father of Captology: BJ Fogg

BJ Fogg, Behavior Scientist at Stanford University, was the first to really lay the foundation for the field of captology. His definitions and avenues for looking at persuasive technology began the discussion that is now, many years later, becoming more widely understood. Fogg also founded the Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab, which has since been renamed the Behavior Design Lab. Over the years the Stanford lab has taken on many projects, including researching the psychology of Facebook and launching the Peace Innovation Lab.

Vocabulary for Thinking About Persuasive Technology

In those early days of captology, BJ Fogg described three types of intent that can form the basis of persuasion: endogenous, exogenous, and autogenous.

- Endogenous intent refers to the original aims of the product designer; for example, the makers of ABC Mouse aim to promote a love of learning in young children.

- Exogenous intent builds on this when a consumer presents a product to another person because of desires of his or her own; this would be the case if a parent introduced her child to ABC Mouse because she wanted to create an attitude or knowledge change in the child.

- Autogenous intent plays out when a user himself decides to try a product to improve his own behaviors, such as an individual purchasing a Continuous Glucose Monitor to discover and avoid foods that cause blood sugar spikes.

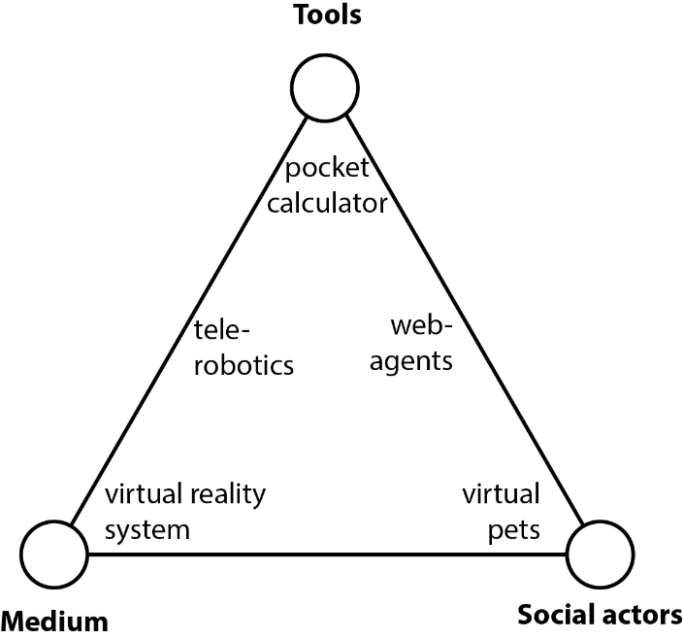

Fogg also thought of persuasive technologies in terms of how they operate. He created the concept of "the functional triad," where technologies act as tools, media, or social actors---or a mix between them. Fogg thought these were all important elements of persuasion, and his optimistic outlook often highlighted how each of them could be used for good. Today, these categories call to mind an analogy that Tristan Harris, president of the Center for Humane Technology, makes in The Social Dilemma: social media is no simple tool, like a bicycle. It's more like a living being, and a drug at the same time. As he says in the film, “It has its own goals and it has its own means of pursuing them by using your own psychology against you.”

Ethical Concerns of Captology

It's unfortunate that Fogg's attempts to raise awareness around this topic were largely ignored for a long time. But now we have social media to help spread the news about social media's harmful and unethical abilities. (Hey, it creates more likes and comments!) Social media's role in our society can influence everything from diet trends to elections. The Social Dilemma itself exhibits all three forms of Fogg's persuasive intent. And most people agree that this a positive example of persuasive technology. There are a host of other ways it can be used to improve our lives---in things like health and safety, mental well-being, and creating a more meaningful and beautiful existence. As with artificial intelligence, it's something potentially very frightening that can instead be used for good. But this isn't always the course it takes. There needs to be an overarching, systemic agreement that persuasive technology must be done ethically and responsibly.

Early technology ethicists Daniel Berdichevsky and Erik Neuenschwander suggested a golden rule back in 1999: creators of persuasive technology should never seek to persuade anyone of something they themselves wouldn't want to be persuaded of. They also highlighted a difference between opting in (like an autogenous user in Fogg's words) and being blindly manipulated (as a victim of profit-driven endogenous intent). These are good starts, but there is so much more discussion---and regulation---that should ideally take place, and it's running behind the actual technologies.

What Can We Do?

One of the common criticisms of The Social Dilemma is that it presents a problem but doesn't offer much in the way of solutions. Indeed, the problem of being manipulated in addictive ways that deteriorate both mental health and societal stability is a daunting one. Even BJ Fogg has been criticized for not investing enough energy into ethics, given his overall optimism about persuasive technology. So, what can we actually do? While this is a massive question that deserves much more thought, here are just a few ideas to start:

On an individual level:

- Consider how the technologies you use affect you: what is the endogenous intent behind it, and does that align with your own goals and intentions?

- Use the technologies that you actively want to opt into and reduce time with technologies you're simply pulled into by addiction or boredom. If you need to, try an app like "Screen Time" to monitor your usage.

- Do the same regarding your kids' use of technology, and manage their use accordingly.

- Ask yourself how you might positively apply your exogenous influence: recommend insightful and helpful technologies to others while discouraging that which doesn't promote productivity or life improvement.

- Create discussions with those around you about captology and persuasive technology ethics. It's great material for both cocktail parties and socially distant video calls!

- If you work in any area of persuasive technology, remember the golden rule. The world you create is the one your kids will grow up in.

On a larger level:

- Advocate for expanded captology and computer science ethics programs in universities and high schools.

- Support any measures that improve privacy regulations or technology-related consumer rights.

- Make ethics a central part of your company, and model it for other organizations to see.

- Follow and work with leaders and partners who prioritize responsibility in innovative technology.

Concluding Thoughts: Don't Stop Here

As technology ethicist James Williams has noted, designers of persuasive technology now essentially have the ability to design users, and even design society. If that thought chills you, learn more about ethical technology efforts like Tristan Harris's, or take a look at some of the positive ways BJ Fogg is aiming to design a better society today.

More on ethics in technology: read our blog post on responsibilities of the tech industry.

Stay connected. Join the Infused Innovations email list!

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Posts

Could Quantum Materials Lead to Emergent Intelligence?

An Election in Today's Tech Age: from Social Media to Artificial Intelligence

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think