Working from Home's Effect on the Brain

If you've shifted to remote work over the past few months, you may have wondered about---or noticed---working from home's effect on the brain. Maybe you feel like it's been exhausting, and you wouldn't be alone in that impression. Not only have many employees personally reported difficulty in their transitions to work at home---there are brainwave studies to prove it. As part of a broad inquiry on how remote work affects employees, Microsoft has tracked trends, surveys, interviews, and EEG measurements to see just how our brains are reacting to collaboration that isn't done in person. The subject groups for these studies were information workers at enterprises of small, medium and large sizes. Here's some of what they've found out about working from home's effect on the brain.

Mental Stress from Remote Work

One Microsoft study followed the brainwave patterns from electroencephalogram (EEG) monitors while teams of two people collaborated, both in-person and remotely. It turned out there were significantly more patterns associated with stress and being overworked when the teammates were working remotely. However, when the partners started with remote work first and then switched to in-person collaboration, their brain patterns showed that they had a harder time with their in-person collaborative tasks than those who started out in-person to begin with. So, while the brain tends to prefer working together in the flesh, it also has a bias against change in either direction. If we start out (or become used to) working in less-than-ideal conditions, we may find that switching to "better" conditions later will present challenges as well. This suggests that people working from home because of COVID-19 have faced more mental strain than before the pandemic, but also that a future switch back to in-person work will likely (at least temporarily) be a challenge on the brain as well.

Video Meetings and Brainwaves

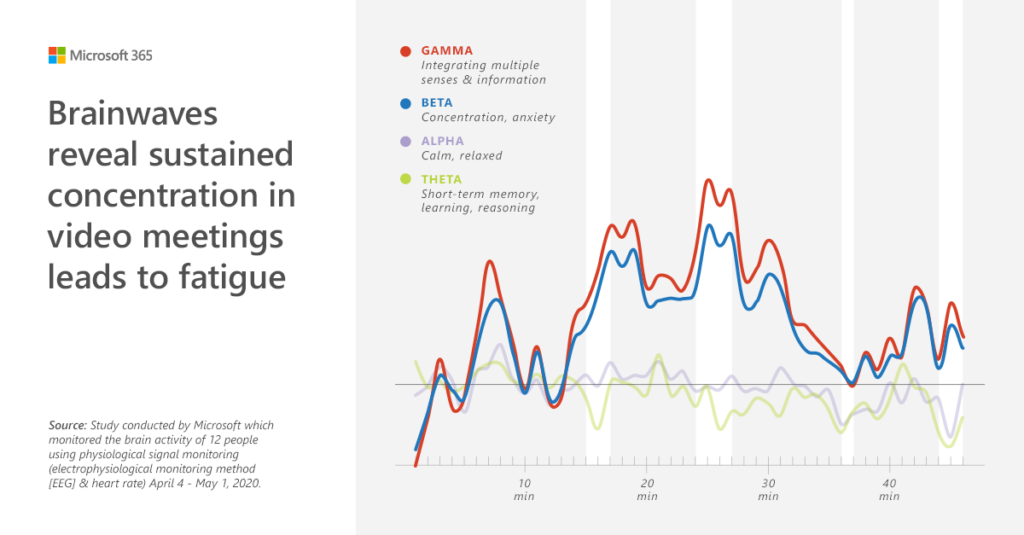

Perhaps not surprisingly, EEG results also showed that our brains are more fatigued while in video meetings than during other tasks such as responding to emails. These meetings demand more sustained attention and require workers to be alert and responsive. This graph shows brainwave patterns as video meetings progress:

Gamma and beta waves, which help us with information processing, critical thinking, and concentration, become much more active during video calls. Alpha and theta waves, more associated with relaxation and restoration, remain lower. After around 30 minutes in a video meeting, the gamma and beta waves begin to fall. This is an indication that fatigue starts to set in as concentration wanes, and is perhaps also the brain's way of regulating these waves to reduce stress. Because as helpful as those gamma and beta waves are for focus, too much of them can lead to anxiety and mental strain.

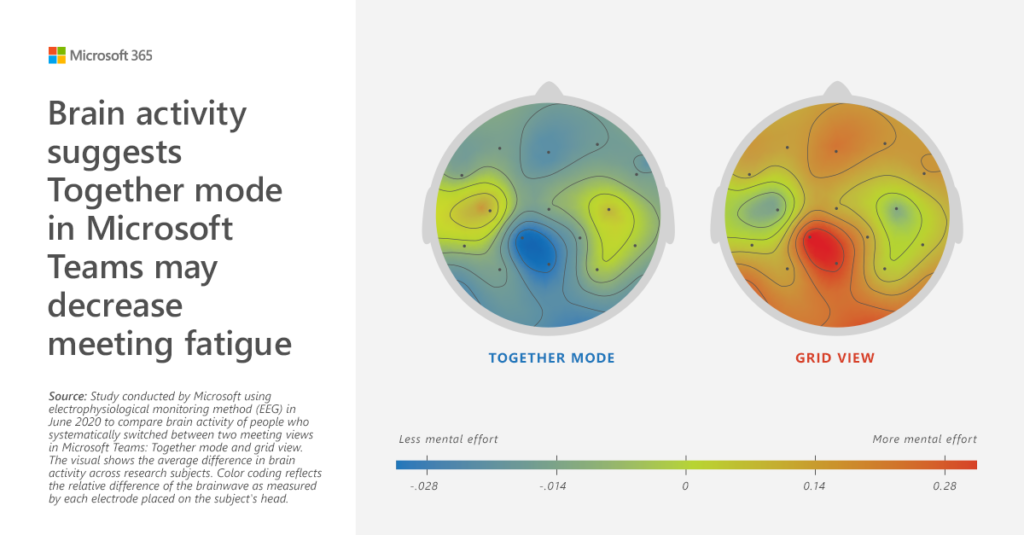

Interestingly, what we see visually on the screen during video meetings makes a difference to our brains. The above image shows how subjects' brain regions exerted effort during meetings in Together Mode vs. Grid View in Microsoft Teams. The same groups of people switched back and forth between these visual options at systematic intervals. Notably, opposite regions of the brain worked harder while processing the two different kinds of views. But it looks like overall, the brain is less fatigued when using Together Mode, probably because it mimics the real-life settings we've been more used to for many years.

Other Effects of Working from Home

Aside from the EEG results, surveys and interviews have shown some other trends among people who've been working from home:

- Increased feelings of empathy and inclusivity. One of the more positive effects of remote working from home is that employees report feeling more empathy toward others than they did before. Often when we are faced with challenges, it makes us more aware and compassionate toward others who are dealing with these struggles too. Respondents also said they feel more valued and included when working remotely, since everyone is in the same situation. Indeed, more empathy on the part of managers can lead to them expressing appreciation more and causing team members to feel more valued.

- More flexible, prolonged hours. Data from Teams usage suggests that in recent months, the range of time in a given day when users are engaged in work-related communications has expanded. They are working more frequently in the mornings, evenings, and weekends than before. Whereas lunch breaks used to correlate with a dip in virtual messaging between colleagues, now workers often continue to send messages while they eat. Some respondents appreciate this flexibility---maybe they are able to take more breaks during the typical workday hours or attend to their kids' needs at home, then catch up on work in the evening. But others may feel that this stretching of work hours endangers the work/life balance they've enjoyed in the past.

Working from Home's Effect on the Brain and Our Lives: Where to Go from Here

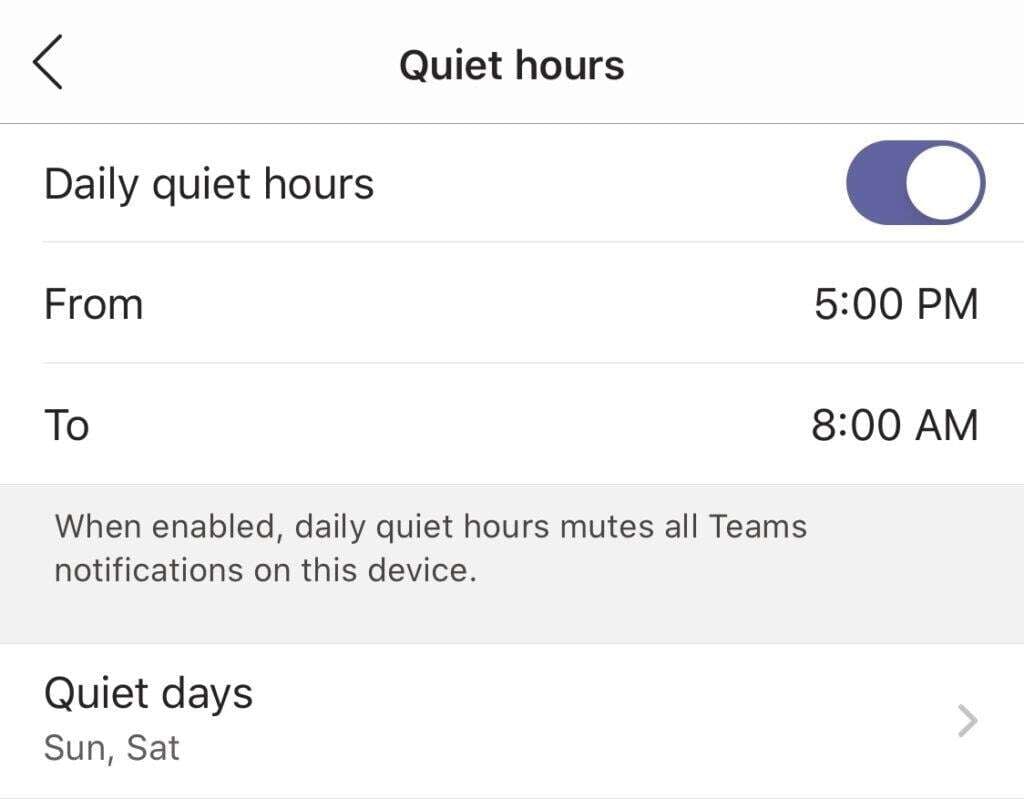

There are lots of ways to make the most of a remote work environment. And since working from home can cause increased fatigue and stress, it's helpful to take measures to allow those alpha and theta waves to come back and restore us. The brain tends to be most productive and stress-free when it is able to move between focused and unfocused times. Optimize this capacity by limiting meetings to 30 minutes, taking breaks when your attention starts to wane, and incorporating meditation or short naps into your day when possible. Organizations might consider something like "Recharge Fridays" (or another workday) in which no meetings will take place and expectations are more flexible. If you use Microsoft Teams, you can set your focus status or quiet hours so that others (including your device) know when it is or isn't a good time to contact or alert you.

As with the current status of COVID-19, it's hard to know how long working from home will continue---or whether it may even become an ongoing way of life post-pandemic. According to Microsoft surveys, 71% of employees would like to be able to continue working from home, at least part time, after the pandemic; 82% of managers plan to continue to have more flexible work-from-home policies than they did before COVID-19. If there's one positive outcome that all of us can develop out of this pandemic, it's flexibility. And flexibility is good for our brains.

Stay connected. Join the Infused Innovations email list!

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Posts

Take a Break! Why Work Breaks are Crucial, Especially if You're Working from Home

How Mixed Reality Can Help with Autism

No Comments Yet

Let us know what you think